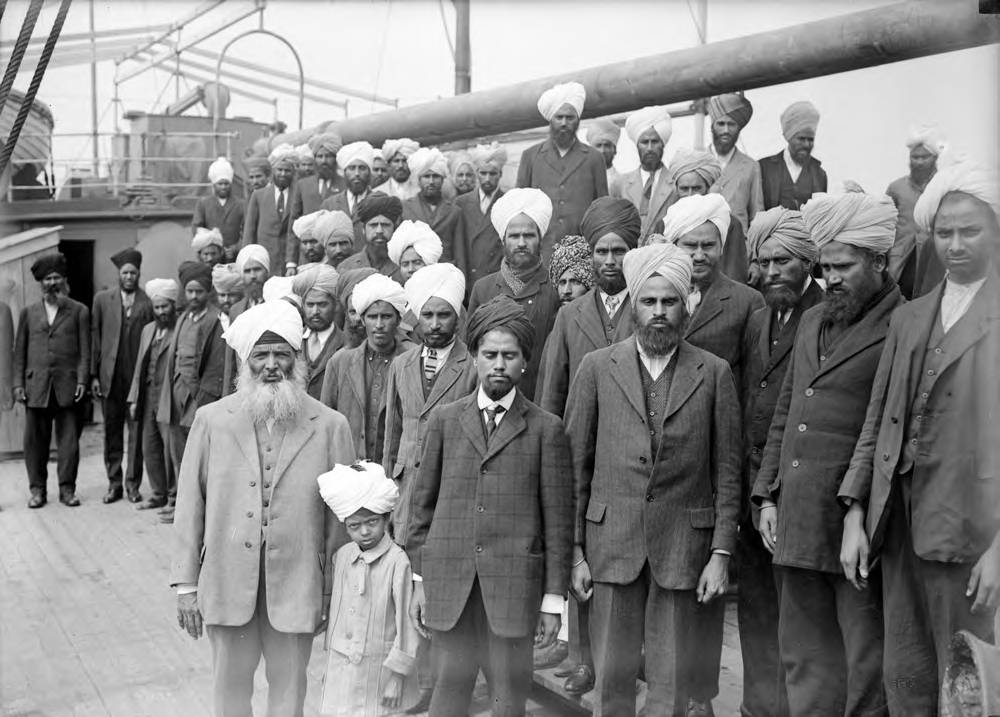

On May 23rd, 1914, the Komagata Maru, a Japanese ship, entered Burrard Inlet outside of Vancouver carrying 376 people looking for a better life in Canada. They were denied entry on a legal technicality. Canada had introduced a law that required immigrants to Canada to arrive by a single, direct journey from their country of origin. This means immigrants from European and other desirable destinations that direct passenger service could emigrate to Canada, and those from more distant and less desirable lands could not. It was part of a series of discriminatory immigration measures (many aimed against Chinese immigration such as the notorious “head tax”) that characterized Canada’s policy through the early part of the twentieth century. It is hard to imagine now the popularity of the song “White Canada forever” then.

Burrard Inlet became the site of a standoff that garnered international attention. The ship lacked sufficient food, water and medicine for the passengers. They were denied proper legal counsel. Eventually, they managed to challenge the denial of their landing and on July 23, 2014 – more or less exactly 100 years ago – the Komagata Maru passengers was compelled to leave Canada.

The Komagata Maru is a symbol not just of Canada’s racist past, but also of the arbitrariness of law. What can the rule of law mean when statutes can be enacted for no legitimate reason, and enforced so as to deny basic rights to the most vulnerable? What moral right did the descendants of immigrants, many of whom had come to Canada in search of a better life, have to deny that same opportunity to others? What is the purpose of Canada if not to serve as a haven for those fleeing harm or seeking help? These are the questions we considered as Osgoode Hall Law School at York University explored the centenary of the Komagata Maru in March of 2014.

Led by Osgoode’s South Asian Law Students’ Association (SALSA), a series of events were staged over a week (which also coincided with Osgoode’s “Diversity Week”), including an exhibit (the Komagata Maru Reflections Project), an award-winning documentary “A Continuous Journey,” followed by a Q+A session with Ali Kazimi, filmmaker and Associate Professor in York’s department of film and several lectures, including one by University of Toronto’s Professor Audrey Macklin, one by Pardeep Nagra, Executive Director of the Sikh Heritage Museum of Canada and a keynote speech from former B.C. Premier Ujjal Dosanjh on “Why Apologizing for Historical Wrongs is Wrong.” It was a remarkable week.

I spent many moments then and since reflecting on the meaning of the Komagata Maru. For the Canadian Jewish community, it is impossible to listen to the story of the Komagata Maru without hearing echoes of the M.S. St. Louis, a ship carrying 907 German Jews seeking a place to escape persecution and the ravages of Nazi Germany, in 1939. The ship was shunned first by Cuba and then by America. Canada did not want the refugees traveling on the vessel either — “none is too many,” an immigration agent would say of Jews such as those aboard the ship in May, 1939 – a phrase Irving Abella memorialized in his 1982 book of the same name which chronicled the anti-Semitism of the Canadian government and its various efforts to prevent Jews trying to escape from Europe from settling in Canada. The St. Louis was within two days of Halifax Harbour when Ottawa, under pressure from high-ranking politicians within, refused to grant the Jewish families a home. Like the Komagata Maru, the St. Louis has been a stain on Canadian history ever since.

Much has changed since the Komagata Maru and St. Louis were shunned. The Canada in which the law students at Osgoode have grown up (and the one I hope they shape once they graduate) has an international reputation for tolerance, celebration of diversity and inclusion. Canada’s Constitution through the Charter of Rights now protects against the kind of discriminatory laws and policies that were used to prevent the landing of these ships. In 2011, the "Wheel of Conscience" was unveiled at Canada’s immigration museum, Pier 21 in Halifax. It is a monument designed by Daniel Libeskind (who was born to Holocaust survivors in Poland) to ensure the memory of the St. Louis lives on. In 2014, Osgoode students in the Anti-Discrimination Intensive will journey to Winnipeg for the opening of Canada’s Museum of Human Rights.

That said, I don’t believe the centenary of the Komagata Maru is a time to reflect on how far we’ve come. Rather, it is a time to remind ourselves how far we have to go. While immigrants and refugees (mostly) no longer arrive in large ships, people seeking a better life in Canada are routinely turned away. They fail to “score” enough “points” to gain entry under Canada’s Immigration Regulations, or their refugee applications are denied because they lack “credibility.” Those seeking entry continue to encounter arbitrariness, unfairness and discrimination. In a sense, it is precisely because Canada now has come to be defined by shared principles around fundamental rights and social justice that our immigration system merits closer scrutiny. The work started by those who fought to allow the Komagata Maru to land, and those who refused to let the memory of the Komagata Maru disappear remains a work in progress for all of us. Just as law provided the pretext for denying entry to the Komagata Maru, so law holds the potential for ensuring that the next ship to appear on the horizon is met with compassion, fairness and justice.

Lorne Sossin is a Professor and Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School, at York University.